How To Find Out Cervical Cancer

| Cervical cancer | |

|---|---|

| |

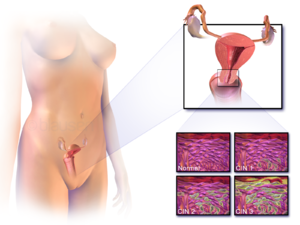

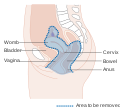

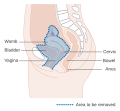

| Location of cervical cancer and an instance of normal and abnormal cells | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | Early: none[2] Later on: vaginal haemorrhage, pelvic pain, pain during sexual intercourse[2] |

| Usual onset | Over 10 to 20 years[3] |

| Types | Squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, others[4] |

| Causes | Human papillomavirus infection (HPV)[5] [six] |

| Chance factors | Smoking, weak immune arrangement, nascence control pills, starting sex at a young age, many sexual partners or a partner with many sexual partners[two] [iv] [7] |

| Diagnostic method | Cervical screening followed by a biopsy[2] |

| Prevention | Regular cervical screening, HPV vaccines, sexual intercourse with condoms,[8] [nine] sexual forbearance |

| Treatment | Surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy[ii] |

| Prognosis | Five-yr survival rate: 68% (US) 46% (India)[10] |

| Frequency | 604,127 new cases (2020)[xi] |

| Deaths | 341,831 (2020)[eleven] |

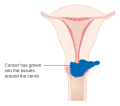

Cervical cancer is a cancer arising from the cervix.[2] It is due to the abnormal growth of cells that accept the ability to invade or spread to other parts of the body.[12] Early on, typically no symptoms are seen.[ii] After symptoms may include abnormal vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain or pain during sexual intercourse.[2] While bleeding afterward sex may not exist serious, it may also indicate the presence of cervical cancer.[xiii]

Human papillomavirus infection (HPV) causes more than 90% of cases;[v] [half dozen] most people who have had HPV infections, however, do not develop cervical cancer.[iii] [xiv] Other risk factors include smoking, a weak immune system, birth command pills, starting sexual activity at a young age, and having many sexual partners, but these are less important.[ii] [4] Genetic factors as well contribute to cervical cancer adventure.[15] Cervical cancer typically develops from precancerous changes over 10 to 20 years.[3] Almost 90% of cervical cancer cases are squamous prison cell carcinomas, 10% are adenocarcinoma, and a small number are other types.[four] Diagnosis is typically past cervical screening followed by a biopsy.[2] Medical imaging is then done to decide whether or non the cancer has spread.[2]

HPV vaccines protect against two to seven high-risk strains of this family of viruses and may prevent up to 90% of cervical cancers.[9] [sixteen] [17] As a risk of cancer notwithstanding exists, guidelines recommend continuing regular Pap tests.[9] Other methods of prevention include having few or no sexual partners and the utilise of condoms.[eight] Cervical cancer screening using the Pap test or acerb acid tin place precancerous changes, which when treated, can prevent the evolution of cancer.[eighteen] Handling may consist of some combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.[2] Five-year survival rates in the United States are 68%.[nineteen] Outcomes, however, depend very much on how early on the cancer is detected.[four]

Worldwide, cervical cancer is both the fourth-near common blazon of cancer and the 4th-most common crusade of decease from cancer in women.[3] In 2022, an estimated 528,000 cases of cervical cancer occurred, with 266,000 deaths.[3] This is about 8% of the full cases and total deaths from cancer.[20] Well-nigh 70% of cervical cancers and 90% of deaths occur in developing countries.[3] [21] In low-income countries, information technology is 1 of the most common causes of cancer death.[18] In adult countries, the widespread use of cervical screening programs has dramatically reduced rates of cervical cancer.[22] Expected scenarios for the reduction of mortality due to cervical cancer worldwide (and especially in low-income countries) have been reviewed, given assumptions with respect to the achievement of recommended prevention targets using triple-intervention strategies defined by WHO.[23] In medical enquiry, the about famous immortalized cell line, known as HeLa, was developed from cervical cancer cells of a woman named Henrietta Lacks.[24]

Signs and symptoms [edit]

The early on stages of cervical cancer may be completely complimentary of symptoms.[5] [22] Vaginal haemorrhage, contact bleeding (one most mutual form being bleeding after sexual intercourse), or (rarely) a vaginal mass may indicate the presence of malignancy. Likewise, moderate pain during sexual intercourse and vaginal discharge are symptoms of cervical cancer.[25] In advanced affliction, metastases may exist present in the abdomen, lungs, or elsewhere.[26]

Symptoms of advanced cervical cancer may include: loss of appetite, weight loss, fatigue, pelvic pain, dorsum hurting, leg pain, swollen legs, heavy vaginal haemorrhage, bone fractures, and (rarely) leakage of urine or feces from the vagina.[27] Bleeding after douching or afterward a pelvic test is a common symptom of cervical cancer.[28]

Causes [edit]

In nearly cases, cells infected with the HPV heal on their own. In some cases, however, the virus continues to spread and becomes an invasive cancer.

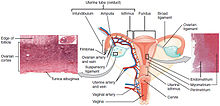

Cervix in relation to upper part of vagina and posterior portion of uterus, showing difference in covering epithelium of inner structures.

Infection with some types of HPV is the greatest take a chance factor for cervical cancer, followed by smoking.[29] HIV infection is also a risk gene.[29] Not all of the causes of cervical cancer are known, still, and several other contributing factors accept been implicated.[30] [31]

Human papillomavirus [edit]

HPV types 16 and 18 are the cause of 75% of cervical cancer cases globally, while 31 and 45 are the causes of another 10%.[32]

Women who have sexual activity with men who have many other sexual partners or women who have many sexual partners have a greater risk.[33] [34]

Of the 150-200 types of HPV known,[35] [36] 15 are classified as loftier-hazard types (xvi, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, and 82), iii equally likely high-take chances (26, 53, and 66), and 12 as low-risk (vi, eleven, 40, 42, 43, 44, 54, 61, seventy, 72, 81, and CP6108).[37]

Genital warts, which are a form of benign tumor of epithelial cells, are besides caused by various strains of HPV. However, these serotypes are ordinarily not related to cervical cancer. Having multiple strains at the same time is common, including those that can crusade cervical cancer along with those that cause warts. Infection with HPV is generally believed to be required for cervical cancer to occur.[38]

Smoking [edit]

Cigarette smoking, both active and passive, increases the risk of cervical cancer. Amid HPV-infected women, current and former smokers have roughly ii to three times the incidence of invasive cancer. Passive smoking is also associated with increased adventure, but to a lesser extent.[39]

Smoking has also been linked to the development of cervical cancer.[forty] [41] [29] Smoking can increase the run a risk in women a few different means, which can be past direct and indirect methods of inducing cervical cancer.[xl] [29] [42] A direct way of contracting this cancer is a smoker has a higher take a chance of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN3) occurring, which has the potential of forming cervical cancer.[twoscore] When CIN3 lesions pb to cancer, most of them have the assistance of the HPV virus, but that is not always the example, which is why it can be considered a directly link to cervical cancer.[42] Heavy smoking and long-term smoking seem to have more of a take chances of getting the CIN3 lesions than lighter smoking or not smoking at all.[43] Although smoking has been linked to cervical cancer, it aids in the evolution of HPV, which is the leading cause of this blazon of cancer.[29] Likewise, not only does it aid in the development of HPV, only also if the adult female is already HPV-positive, she is at an even greater likelihood of contracting cervical cancer.[43]

Oral contraceptives [edit]

Long-term utilize of oral contraceptives is associated with increased risk of cervical cancer in women who have had HPV. Women who have used oral contraceptives for v to ix years have about iii times the incidence of invasive cancer, and those who used them for 10 years or longer accept about four times the risk.[39]

Multiple pregnancies [edit]

Having many pregnancies is associated with an increased take chances of cervical cancer. Among HPV-infected women, those who accept had seven or more total-term pregnancies have around four times the take a chance of cancer compared with women with no pregnancies, and 2 to three times the run a risk of women who have had ane or two full-term pregnancies.[39]

Diagnosis [edit]

Cervical cancer seen on a T2-weighted sagittal MR image of the pelvis.

Biopsy [edit]

The Pap examination tin can be used every bit a screening test, but produces a false negative in up to 50% of cases of cervical cancer.[44] [45] Other concerns is the price of doing Pap tests, which brand them unaffordable in many areas of the earth.[46]

Confirmation of the diagnosis of cervical cancer or precancer requires a biopsy of the neck. This is frequently done through colposcopy, a magnified visual inspection of the cervix aided by using a dilute acetic acrid (e.g. vinegar) solution to highlight abnormal cells on the surface of the cervix,[5] with visual contrast provided by staining the normal tissues a mahogany brown with Lugol'southward iodine.[47] Medical devices used for biopsy of the neck include punch forceps. Colposcopic impression, the approximate of disease severity based on the visual inspection, forms part of the diagnosis. Further diagnostic and treatment procedures are loop electrical excision procedure and cervical conization, in which the inner lining of the cervix is removed to exist examined pathologically. These are carried out if the biopsy confirms severe cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.[ medical commendation needed ]

This large squamous carcinoma (bottom of picture) has obliterated the cervix and invaded the lower uterine segment. The uterus also has a round leiomyoma up higher.

Often earlier the biopsy, the md asks for medical imaging to rule out other causes of adult female's symptoms. Imaging modalities such equally ultrasound, CT browse, and MRI have been used to look for alternate affliction, spread of the tumor, and effect on adjacent structures. Typically, they appear as heterogeneous mass on the neck.[48]

Interventions such every bit playing music during the procedure and viewing the procedure on a monitor can reduce the anxiety associated with the examination.[49]

Precancerous lesions [edit]

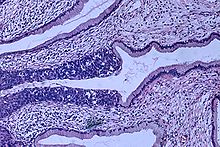

Histopathologic prototype (H&East stain) of carcinoma in situ (also called CIN3), phase 0: The normal architecture of stratified squamous epithelium is replaced by irregular cells that extend throughout its full thickness. Normal columnar epithelium is also seen.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, the potential precursor to cervical cancer, is frequently diagnosed on exam of cervical biopsies by a pathologist. For premalignant dysplastic changes, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grading is used.[ citation needed ]

The naming and histologic classification of cervical carcinoma forerunner lesions has changed many times over the 20th century. The World Health Organization classification[50] [51] system was descriptive of the lesions, naming them mild, moderate, or astringent dysplasia or carcinoma in situ (CIS). The term cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) was developed to place emphasis on the spectrum of aberration in these lesions, and to help standardize treatment.[51] It classifies mild dysplasia every bit CIN1, moderate dysplasia equally CIN2, and severe dysplasia and CIS equally CIN3. More than recently, CIN2 and CIN3 accept been combined into CIN2/3. These results are what a pathologist might report from a biopsy.[ citation needed ]

These should non exist dislocated with the Bethesda system terms for Pap test (cytopathology) results. Amidst the Bethesda results: Low-class squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL). An LSIL Pap may correspond to CIN1, and HSIL may correspond to CIN2 and CIN3,[51] simply they are results of different tests, and the Pap examination results need not lucifer the histologic findings.[ medical citation needed ]

Cancer subtypes [edit]

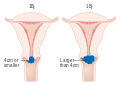

The location of cervical cancer tin be described in terms of quadrants, or corresponding to a clock face up when the subject is in supine position.

Histologic subtypes of invasive cervical carcinoma include:[52] [53] Though squamous prison cell carcinoma is the cervical cancer with the most incidence, the incidence of adenocarcinoma of the cervix has been increasing in recent decades.[5] Endocervical adenocarcinoma represents 20–25% of the histological types of cervical carcinoma. Gastric-type mucinous adenocarcinoma of the cervix is a rare type of cancer with aggressive behavior. This type of malignancy is not related to loftier-adventure human papillomavirus (HPV).[54]

- Squamous cell carcinoma (near 80–85%[55] [56])

- adenocarcinoma (about 15% of cervical cancers in the UK[50])

- Adenosquamous carcinoma

- Small cell carcinoma

- Neuroendocrine neoplasm

- Glassy jail cell carcinoma

- Villoglandular adenocarcinoma

Noncarcinoma malignancies which can rarely occur in the cervix include melanoma and lymphoma. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage does not incorporate lymph node involvement in contrast to the TNM staging for most other cancers. For cases treated surgically, information obtained from the pathologist tin can be used in assigning a separate pathologic stage, but is not to supersede the original clinical phase.[ citation needed ]

Staging [edit]

Cervical cancer is staged by the FIGO system, which is based on clinical examination rather than surgical findings. Prior to the 2022 revisions to FIGO staging, the system allowed simply these diagnostic tests to be used in determining the phase: palpation, inspection, colposcopy, endocervical curettage, hysteroscopy, cystoscopy, proctoscopy, intravenous urography, and X-ray exam of the lungs and skeleton, and cervical conization. However, the current system allows use of whatsoever imaging or pathological methods for staging.[57]

-

Stage 1A cervical cancer

-

Phase 1B cervical cancer

-

Phase 2A cervical cancer

-

Stage 2B cervical cancer

-

Stage 3B cervical cancer

-

Stage 4A cervical cancer

-

Stage 4B cervical cancer

Prevention [edit]

Screening [edit]

Cervical screening test vehicle in Taiwan.

Negative visual inspection with acetic acid of the cervix.

Positive visual inspection with acetic acid of the cervix for CIN-1.

Checking cervical cells with the Papanicolaou test (Pap test) for cervical pre-cancer has dramatically reduced the number of cases of, and mortality from, cervical cancer.[22] Liquid-based cytology may reduce the number of inadequate samples.[58] [59] [60] Pap test screening every iii to five years with appropriate follow-up can reduce cervical cancer incidence upward to eighty%.[61] Abnormal results may suggest the presence of precancerous changes, allowing test and possible preventive treatment, known equally colposcopy. The treatment of low-course lesions may adversely affect subsequent fertility and pregnancy.[39] Personal invitations encouraging women to go screened are effective at increasing the likelihood they will practice so. Educational materials as well assistance increase the likelihood women will get for screening, but they are not as effective every bit invitations.[62]

Co-ordinate to the 2022 European guidelines, the age at which to start screening ranges between twenty and thirty years of age, but preferentially not before historic period 25 or 30 years, and depends on burden of the disease in the population and the available resources.[61]

In the United States, screening is recommended to brainstorm at age 21, regardless of age at which a woman began having sex or other risk factors.[63] Pap tests should be done every three years betwixt the ages of 21 and 65.[63] In women over the age of 65, screening may exist discontinued if no abnormal screening results were seen within the previous 10 years and no history of CIN2 or higher exists.[63] [64] [65] HPV vaccination status does non change screening rates.[64]

A number of recommended options be for screening those 30 to 65.[66] This includes cervical cytology every iii years, HPV testing every 5 years, or HPV testing together with cytology every 5 years.[66] [64] Screening is non benign earlier age 25, as the rate of illness is low. Screening is not benign in women older than 60 years if they have a history of negative results.[39] The American Gild of Clinical Oncology guideline has recommend for different levels of resource availability.[67]

Pap tests have non been as effective in developing countries.[68] This is in part because many of these countries have an impoverished health care infrastructure, likewise few trained and skilled professionals to obtain and interpret Pap tests, uninformed women who go lost to follow-upward, and a lengthy turn-around time to get results.[68] Visual inspection with acerb acid and HPV Dna testing accept been tried, though with mixed success.[68]

Bulwark protection [edit]

Bulwark protection or spermicidal gel use during sexual intercourse decreases, but does not eliminate risk of transmitting the infection,[39] though condoms may protect against genital warts.[69] They also provide protection confronting other sexually transmitted infections, such equally HIV and Chlamydia, which are associated with greater risks of developing cervical cancer.[ medical commendation needed ]

Vaccination [edit]

Three HPV vaccines (Gardasil, Gardasil ix, and Cervarix) reduce the take a chance of cancerous or precancerous changes of the cervix and perineum by about 93% and 62%, respectively.[lxx] The vaccines are betwixt 92% and 100% effective confronting HPV 16 and 18 up to at least 8 years.[39]

HPV vaccines are typically given to age 9 to 26, as the vaccine is most effective if given before infection occurs. The duration of effectiveness and whether a booster will be needed is unknown. The high price of this vaccine has been a cause for business concern. Several countries have considered (or are considering) programs to fund HPV vaccination. The American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline has recommendations for different levels of resource availability.[67]

Since 2022, immature women in Japan take been eligible to receive the cervical cancer vaccination for free.[71] In June 2022, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare mandated that, earlier administering the vaccine, medical institutions must inform women that the ministry does non recommend it.[71] However, the vaccine is still available at no cost to Japanese women who choose to have the vaccination.[71]

Diet [edit]

Vitamin A is associated with a lower risk[72] as are vitamin B12, vitamin C, vitamin E, and beta-Carotene.[73]

Handling [edit]

The treatment of cervical cancer varies worldwide, largely due to access to surgeons skilled in radical pelvic surgery, and the emergence of fertility-sparing therapy in adult nations. Less advanced stages of cervical cancer typically have treatment options that allow fertility to be maintained, if the patient desires.[74] Because cervical cancers are radiosensitive, radiation may be used in all stages where surgical options do non exist. Surgical intervention may accept better outcomes than radiological approaches.[75] In addition, chemotherapy can be used to treat cervical cancer, and has been found to be more constructive than radiations alone.[76] Evidence suggests chemoradiotherapy may increment overall survival and reduce the risk of disease recurrence compared to radiotherapy alone.[77] Peri-operative care approaches, such every bit 'fast-track surgery' or 'enhanced recovery programmes' may lower surgical stress and improve recovery after gynaecological cancer surgery.[78]

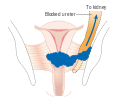

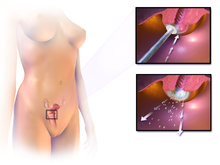

Microinvasive cancer (stage IA) may be treated by hysterectomy (removal of the whole uterus including office of the vagina).[79] For stage IA2, the lymph nodes are removed, besides. Alternatives include local surgical procedures such as a loop electric excision procedure or cone biopsy.[fourscore] [81] A systematic review concluded that more evidence is needed to inform decisions nigh different surgical techniques for women with cervical cancer at stage IA2.[82]

If a cone biopsy does non produce clear margins[83] (findings on biopsy showing that the tumor is surrounded by cancer free tissue, suggesting all of the tumor is removed), one more than possible treatment option for women who want to preserve their fertility is a trachelectomy.[84] This attempts to surgically remove the cancer while preserving the ovaries and uterus, providing for a more than bourgeois functioning than a hysterectomy. Information technology is a viable option for those in stage I cervical cancer which has not spread; however, it is not nonetheless considered a standard of care,[85] every bit few doctors are skilled in this procedure. Even the well-nigh experienced surgeon cannot promise that a trachelectomy can be performed until subsequently surgical microscopic test, as the extent of the spread of cancer is unknown. If the surgeon is not able to microscopically confirm clear margins of cervical tissue one time the woman is nether general anesthesia in the operating room, a hysterectomy may still be needed. This can just be done during the same functioning if the woman has given prior consent. Due to the possible risk of cancer spread to the lymph nodes in stage 1B cancers and some stage 1A cancers, the surgeon may also demand to remove some lymph nodes from around the uterus for pathologic evaluation.[ citation needed ]

A radical trachelectomy can exist performed abdominally[86] or vaginally[87] and opinions are conflicting as to which is meliorate.[88] A radical abdominal trachelectomy with lymphadenectomy usually simply requires a two- to three-solar day infirmary stay, and most women recover very quickly (about six weeks). Complications are uncommon, although women who are able to conceive after surgery are susceptible to preterm labor and possible late miscarriage.[89] A wait of at to the lowest degree i year is generally recommended earlier attempting to become pregnant after surgery.[xc] Recurrence in the residual cervix is very rare if the cancer has been cleared with the trachelectomy.[85] Yet, women are recommended to practice vigilant prevention and follow-upwardly care including Pap screenings/colposcopy, with biopsies of the remaining lower uterine segment every bit needed (every three–4 months for at least 5 years) to monitor for any recurrence in add-on to minimizing whatsoever new exposures to HPV through safe sex practices until one is actively trying to excogitate.[ citation needed ]

Early stages (IB1 and IIA less than 4 cm) tin can exist treated with radical hysterectomy with removal of the lymph nodes or radiation therapy. Radiations therapy is given as external axle radiotherapy to the pelvis and brachytherapy (internal radiation). Women treated with surgery who have high-adventure features establish on pathologic test are given radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy to reduce the gamble of relapse.[ citation needed ] A Cochrane review has constitute moderate-certainty evidence that radiations decreases the risk of illness progression in people with stage IB cervical cancer, when compared to no further treatment.[91] However, little show was found on its effects on overall survival.[91]

Brachytherapy for cervical cancer

Larger early-phase tumors (IB2 and IIA more than 4 cm) may be treated with radiations therapy and cisplatin-based chemotherapy, hysterectomy (which then normally requires adjuvant radiations therapy), or cisplatin chemotherapy followed by hysterectomy. When cisplatin is present, it is thought to exist the almost agile single agent in periodic diseases.[92] Such addition of platinum-based chemotherapy to chemoradiation seems non only to meliorate survival just also reduces risk of recurrence in women with early stage cervical cancer (IA2-IIA).[93] A Cochrane review found a lack of evidence on the benefits and harms of master hysterectomy compared to main chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer in phase IB2.[94]

Advanced-stage tumors (IIB-IVA) are treated with radiation therapy and cisplatin-based chemotherapy. On 15 June 2006, the US Nutrient and Drug Administration approved the use of a combination of two chemotherapy drugs, hycamtin and cisplatin, for women with late-stage (IVB) cervical cancer treatment.[95] Combination handling has significant chance of neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia side effects.[96]

There is insufficient evidence whether anticancer drugs after standard intendance assist women with locally advanced cervical cancer to alive longer.[97]

For surgery to be curative, the entire cancer must be removed with no cancer found at the margins of the removed tissue on examination under a microscope.[98] This procedure is known as exenteration.[98]

No evidence is available to propose that any course of follow‐up approach is better or worse in terms of prolonging survival, improving quality of life or guiding the management of bug that can arise because of the treatment and that in the case of radiotherapy treatment worsen with time.[99] A 2022 review found no controlled trials regarding the efficacy and safe of interventions for vaginal bleeding in women with advanced cervical cancer.[100]

Tisotumab vedotin (Tivdak) was approved for medical use in the The states in September 2022.[101] [102]

-

Diagram showing the area removed with a posterior surgery

-

Diagram showing the area removed with a total operation

-

Diagram showing the area removed with an inductive operation

Prognosis [edit]

| | This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: extremely dated sources throughout prognosis and epidemiology. (March 2022) |

Stage [edit]

Prognosis depends on the stage of the cancer. The chance of a survival rate is nigh 100% for women with microscopic forms of cervical cancer.[103] With treatment, the five-year relative survival rate for the earliest phase of invasive cervical cancer is 92%, and the overall (all stages combined) five-year survival rate is about 72%. These statistics may be improved when applied to women newly diagnosed, bearing in heed that these outcomes may be partly based on the country of treatment five years ago when the women studied were first diagnosed.[104]

With treatment, 80–ninety% of women with phase I cancer and 60–75% of those with stage Two cancer are alive 5 years after diagnosis. Survival rates decrease to 30–twoscore% for women with phase III cancer and xv% or fewer of those with stage 4 cancer five years after diagnosis.[105] Recurrent cervical cancer detected at its earliest stages might be successfully treated with surgery, radiations, chemotherapy, or a combination of the three. Nearly 35% of women with invasive cervical cancer have persistent or recurrent disease after treatment.[106]

By state [edit]

5 year survival in the U.s.a. for White women is 69% and for Black women is 57%.[ needs update ] [107]

Regular screening has meant that precancerous changes and early-stage cervical cancers have been detected and treated early. Figures suggest that cervical screening is saving 5,000 lives each year in the UK by preventing cervical cancer.[108] About 1,000 women per yr die of cervical cancer in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland. All of the Nordic countries accept cervical cancer-screening programs in place.[109] The Pap test was integrated into clinical practice in the Nordic countries in the 1960s.[109]

In Africa outcomes are often worse as diagnosis is frequently at a latter phase of affliction.[110] In a scoping review of publicly-available cervical cancer prevention and control plans from African countries, plans tended to emphasize survivorship rather than early on HPV diagnosis and prevention.[111]

Epidemiology [edit]

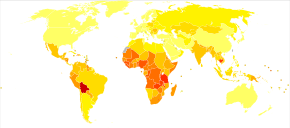

Historic period-standardized death from cervical cancer per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004[112]

| no data <2.iv two.4-4.8 4.8-7.2 vii.2-nine.6 9.half dozen-12 12-xiv.4 | 14.four-sixteen.eight xvi.8-19.2 19.2-21.6 21.six–24 24–26.4 >26.4 |

Worldwide, cervical cancer is both the 4th-most common cause of cancer and deaths from cancer in women.[3] In 2022, 570,000 cases of cervical cancer were estimated to accept occurred, with over 300,000 deaths.[113] It is the second-most common cause of female-specific cancer subsequently breast cancer, accounting for around viii% of both total cancer cases and total cancer deaths in women.[20] Near 80% of cervical cancers occur in developing countries.[114] It is the most frequently detected cancer during pregnancy, with an occurrence of one.v to 12 for every 100,000 pregnancies.[115]

Australia [edit]

| | This section needs to be updated. (September 2022) |

Australia had 734 cases of cervical cancer in 2005. The number of women diagnosed with cervical cancer has dropped on average past 4.five% each yr since organised screening began in 1991 (1991–2005).[116] Regular twice-yearly Pap tests tin reduce the incidence of cervical cancer upwardly to 90% in Commonwealth of australia, and salve 1,200 Australian women from dying from the disease each year.[117] Information technology is predicted that considering of the success of the primary HPV testing plan there will be fewer than four new cases per 100 000 women annually past 2028.[118]

Canada [edit]

| | This department needs to be updated. (September 2022) |

In Canada, an estimated 1,300 women will accept been diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2008 and 380 will take died.[119]

India [edit]

In India, the number of people with cervical cancer is rising, but overall the age-adapted rates are decreasing.[120] Usage of condoms in the female population has improved the survival of women with cancers of the cervix.[121]

European Wedlock [edit]

| | This department needs to exist updated. (September 2022) |

In the European Union, about 34,000 new cases per year and over 16,000 deaths due to cervical cancer occurred in 2004.[61]

Uk [edit]

| | This section needs to exist updated. (September 2022) |

Cervical cancer is the 12th-near common cancer in women in the UK (around iii,100 women were diagnosed with the disease in 2022), and accounts for one% of cancer deaths (around 920 died in 2022).[122] With a 42% reduction from 1988 to 1997, the NHS-implemented screening programme has been highly successful, screening the highest-risk age group (25–49 years) every 3 years, and those ages 50–64 every 5 years.[ citation needed ]

Usa [edit]

| | This section needs to exist updated. (September 2022) |

An estimated thirteen,170 new cervical cancers and 4,250 cervical cancer deaths will occur in the The states in 2022.[123] The median age at diagnosis is 50. The rates of new cases in the U.s.a. was 7.3 per 100,000 women, based on rates from 2022 to 2022. Cervical cancer deaths decreased past approximately 74% in the concluding 50 years, largely due to widespread Pap test screening.[124] The annual direct medical cost of cervical cancer prevention and treatment prior to introduction of the HPV vaccine was estimated at $half dozen billion.[124]

History [edit]

- 400 BCE — Hippocrates noted that cervical cancer was incurable.

- 1925 — Hinselmann invented the colposcope.

- 1928 — Papanicolaou adult the Papanicolaou technique.

- 1941 — Papanicolaou and Traut: Pap test screening began.

- 1946 — Aylesbury spatula was developed to scrape the cervix, collecting the sample for the Pap test.

- 1951 — Starting time successful in-vitro cell line, HeLa, derived from biopsy of cervical cancer of Henrietta Lacks.

- 1976 — Harald zur Hausen and Gisam found HPV DNA in cervical cancer and genital warts; Hausen later won the Nobel Prize for his piece of work.[125]

- 1988 — Bethesda System for reporting Pap results was developed.

- 2006 — First HPV vaccine was approved by the FDA.

- 2015 — HPV Vaccine shown to protect against infection at multiple torso sites.[126]

- 2018 — Bear witness for single-dose protection with HPV vaccine.[127]

Epidemiologists working in the early 20th century noted that cervical cancer behaved like a sexually transmitted disease. In summary:

- Cervical cancer was noted to exist common in female sexual practice workers.

- It was rare in nuns, except for those who had been sexually active before entering the convent (Rigoni in 1841).

- It was more common in the second wives of men whose first wives had died from cervical cancer.

- It was rare in Jewish women.[128]

- In 1935, Syverton and Berry discovered a relationship between RPV (Rabbit Papillomavirus) and skin cancer in rabbits (HPV is species-specific and therefore cannot be transmitted to rabbits).[ citation needed ]

These historical observations suggested that cervical cancer could be acquired by a sexually transmitted agent. Initial research in the 1940s and 1950s attributed cervical cancer to smegma (eastward.g. Heins et al. 1958).[129] During the 1960s and 1970s it was suspected that infection with canker simplex virus was the cause of the disease. In summary, HSV was seen every bit a likely crusade because information technology is known to survive in the female reproductive tract, to be transmitted sexually in a fashion compatible with known gamble factors, such as promiscuity and low socioeconomic status.[130] Herpes viruses were also implicated in other malignant diseases, including Burkitt'due south lymphoma, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Marek's disease and the Lucké renal adenocarcinoma. HSV was recovered from cervical tumour cells.

A clarification of man papillomavirus (HPV) past electron microscopy was given in 1949, and HPV-DNA was identified in 1963.[131] Information technology was not until the 1980s that HPV was identified in cervical cancer tissue.[132] It has since been demonstrated that HPV is implicated in almost all cervical cancers.[133] Specific viral subtypes implicated are HPV 16, 18, 31, 45 and others.

In piece of work that was initiated in the mid 1980s, the HPV vaccine was adult, in parallel, past researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center, the University of Rochester, the University of Queensland in Commonwealth of australia, and the U.S. National Cancer Institute.[134] In 2006, the U.Southward. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) canonical the start preventive HPV vaccine, marketed by Merck & Co. nether the trade name Gardasil.

In November 2022, the Globe Health System, under backing from the World Wellness Assembly, set out a strategy to eliminate cervical cancer past 2050. The strategy involves vaccinating 90% of girls by the historic period of xv, screening 70% of women by the age of 35 and once again by the age of 45, and treating 90% of women identified with cervical disease.[135]

Club and culture [edit]

Commonwealth of australia [edit]

In Australia, Aboriginal women are more five times more than probable to die from cervical cancer than non-Aboriginal women, suggesting that Ancient women are less likely to take regular Pap tests.[136] In that location are several factors that may limit indigenous women from engaging in regular cervical screening practices, including sensitivity in discussing the topic in Aboriginal communities, embarrassment, feet and fear about the procedure.[137] Difficulty in accessing screening services (for example, ship difficulties) and a lack of female GPs, trained Pap test providers and trained female Aboriginal Health Workers are also issues.[137]

The Australian Cervical Cancer Foundation (ACCF), founded in 2008, promotes 'women's wellness by eliminating cervical cancer and enabling treatment for women with cervical cancer and related wellness bug, in Australia and in developing countries.'[138] Ian Frazer, one of the developers of the Gardasil cervical cancer vaccine, is the scientific advisor to ACCF.[139] Janette Howard, the wife of the and so-Prime Government minister of Australia, John Howard, was diagnosed with cervical cancer in 1996, and starting time spoke publicly about the disease in 2006.[140]

Us [edit]

A 2007 survey of American women establish forty% had heard of HPV infection and less than half of those knew information technology causes cervical cancer.[141] Over a longitudinal study from 1975 to 2000, it was found that people of lower socioeconomic census brackets had higher rates of late-phase cancer diagnosis and higher morbidity rates. After decision-making for phase, in that location still existed differences in survival rates.[142]

References [edit]

- ^ "CERVICAL | pregnant in the Cambridge English language Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org . Retrieved five October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k fifty "Cervical Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)". NCI. fourteen March 2022. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f 1000 World Cancer Written report 2022. Globe Health Arrangement. 2022. pp. Chapter 5.12. ISBN978-9283204299.

- ^ a b c d e "Cervical Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)". National Cancer Institute. 14 March 2022. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 718–721. ISBN978-one-4160-2973-1.

- ^ a b Kufe, Donald (2009). The netherlands-Frei cancer medicine (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 1299. ISBN9781607950141. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022.

- ^ Bosch FX, de Sanjosé Due south (2007). "The epidemiology of human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer". Disease Markers. 23 (iv): 213–27. doi:10.1155/2007/914823. PMC3850867. PMID 17627057.

- ^ a b "Cervical Cancer Prevention (PDQ®)". National Cancer Institute. 27 February 2022. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "Homo Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines". National Cancer Institute. 29 December 2022. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Global Cancer Facts & Figures 3rd Edition" (PDF). 2022. p. nine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ a b Sung, Hyuna; Ferlay, Jacques; Siegel, Rebecca 50.; Laversanne, Mathieu; Soerjomataram, Isabelle; Jemal, Ahmedin; Bray, Freddie (2021). "Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Bloodshed Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 71 (3): 209–249. doi:x.3322/caac.21660. ISSN 1542-4863. PMID 33538338. S2CID 231804598.

- ^ "Defining Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 17 September 2007. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved ten June 2022.

- ^ Tarney CM, Han J (2014). "Postcoital haemorrhage: a review on etiology, diagnosis, and management". Obstetrics and Gynecology International. 2014: 192087. doi:x.1155/2014/192087. PMC4086375. PMID 25045355.

- ^ Dunne EF, Park IU (December 2022). "HPV and HPV-associated diseases". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 27 (four): 765–78. doi:x.1016/j.idc.2013.09.001. PMID 24275269.

- ^ Ramachandran D, Dörk T (Oct 2022). "Genomic gamble factors for cervical cancer". Cancers. 13 (20): 5137. doi:x.3390/cancers13205137. PMC8533931. PMID 34680286.

- ^ "FDA approves Gardasil 9 for prevention of certain cancers acquired by 5 additional types of HPV". U.South. Nutrient and Drug Administration. 10 December 2022. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Tran NP, Hung CF, Roden R, Wu TC (2014). Control of HPV infection and related cancer through vaccination. Recent Results in Cancer Inquiry. Vol. 193. pp. 149–71. doi:ten.1007/978-iii-642-38965-8_9. ISBN978-3-642-38964-1. PMID 24008298.

- ^ a b Earth Health Organization (February 2022). "Fact sheet No. 297: Cancer". Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Neck Uteri Cancer". NCI. National Cancer Plant. 10 November 2022. Archived from the original on vi July 2022. Retrieved eighteen June 2022.

- ^ a b Globe Cancer Report 2022. World Wellness Organization. 2022. pp. Chapter 1.1. ISBN978-9283204299.

- ^ "Cervical cancer prevention and command saves lives in the Republic of korea". World Health Organization . Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Canavan TP, Doshi NR (March 2000). "Cervical cancer". American Family Md. 61 (5): 1369–76. PMID 10735343. Archived from the original on 6 Feb 2005.

- ^ Canfell, Karen; Kim, Jane J.; Brisson, Marc; Keane, Adam; Simms, Kate T.; Caruana, Michael; Burger, Emily A.; Martin, Dave; Nguyen, Diep T. Due north.; Bénard, Élodie; Sy, Stephen (22 Feb 2022). "Mortality impact of achieving WHO cervical cancer elimination targets: a comparative modelling assay in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries". Lancet. 395 (10224): 591–603. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(twenty)30157-4. ISSN 1474-547X. PMC7043006. PMID 32007142.

- ^ Jr, Charles Due east. Carraher (2014). Carraher'southward polymer chemistry (9th ed.). Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis. p. 385. ISBN9781466552036. Archived from the original on 22 Oct 2022.

- ^ "Cervical Cancer Symptoms, Signs, Causes, Stages & Handling". medicinenet.com.

- ^ Cheng Ten, Li H, Wu 10 (July 2022). "Advances in diagnosis and treatment of metastatic cervical cancer". Journal of Gynecologic Oncology. 27 (4): e43. doi:10.3802/jgo.2016.27.e43. PMC4864519. PMID 27171673.

- ^ Nanda, Rita (9 June 2006). "Cervical cancer". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on eleven October 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^ "Cervical Cancer Prevention and Early Detection". Cancer. Archived from the original on ten July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Gadducci A, Barsotti C, Cosio Due south, Domenici L, Riccardo Genazzani A (August 2022). "Smoking habit, allowed suppression, oral contraceptive use, and hormone replacement therapy employ and cervical carcinogenesis: a review of the literature". Gynecological Endocrinology. 27 (8): 597–604. doi:10.3109/09513590.2011.558953. PMID 21438669. S2CID 25447563.

- ^ Stuart Campbell; Ash Monga (2006). Gynaecology past Ten Teachers (18 ed.). Hodder Education. ISBN978-0-340-81662-2.

- ^ "Cervical Cancer Symptoms, Signs, Causes, Stages & Treatment". medicinenet.com.

- ^ Dillman, Robert K.; Oldham, Robert O., eds. (2009). Principles of cancer biotherapy (5th ed.). Dordrecht: Springer. p. 149. ISBN9789048122899. Archived from the original on 29 October 2022.

- ^ "What Causes Cancer of the Cervix?". American Cancer Society. xxx November 2006. Archived from the original on xiii October 2007. Retrieved ii Dec 2007.

- ^ Marrazzo JM, Koutsky LA, Kiviat NB, Kuypers JM, Stine M (June 2001). "Papanicolaou test screening and prevalence of genital homo papillomavirus amongst women who have sex activity with women". American Periodical of Public Wellness. 91 (6): 947–52. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.6.947. PMC1446473. PMID 11392939.

- ^ "HPV Blazon-Detect". Medical Diagnostic Laboratories. xxx Oct 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved two December 2007.

- ^ Gottlieb, Nicole (24 April 2002). "A Primer on HPV". Benchmarks. National Cancer Establish. Archived from the original on 26 October 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^ Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé Due south, Herrero R, Castellsagué 10, Shah KV, et al. (February 2003). "Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer" (PDF). The New England Periodical of Medicine. 348 (six): 518–27. doi:ten.1056/NEJMoa021641. hdl:2445/122831. PMID 12571259.

- ^

- ^ a b c d eastward f g National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute: PDQ® Cervical Cancer Prevention Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Plant. Engagement last modified 5 January 2022. Retrieved half-dozen April 2022.

- ^ a b c Luhn P, Walker J, Schiffman G, Zuna RE, Dunn ST, Gold MA, et al. (February 2022). "The role of co-factors in the progression from human papillomavirus infection to cervical cancer". Gynecologic Oncology. 128 (2): 265–70. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.xi.003. PMC4627848. PMID 23146688.

- ^ Remschmidt C, Kaufmann AM, Hagemann I, Vartazarova E, Wichmann O, Deleré Y (March 2022). "Risk factors for cervical human being papillomavirus infection and high-class intraepithelial lesion in women aged 20 to 31 years in Germany". International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 23 (3): 519–26. doi:10.1097/IGC.0b013e318285a4b2. PMID 23360813. S2CID 205679729.

- ^ a b Agorastos T, Miliaras D, Lambropoulos AF, Chrisafi S, Kotsis A, Manthos A, Bontis J (July 2005). "Detection and typing of human papillomavirus DNA in uterine cervices with coexistent grade I and grade III intraepithelial neoplasia: biologic progression or independent lesions?". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 121 (i): 99–103. doi:ten.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.11.024. PMID 15949888.

- ^ a b Jensen KE, Schmiedel S, Frederiksen K, Norrild B, Iftner T, Kjær SK (November 2022). "Chance for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia course three or worse in relation to smoking among women with persistent homo papillomavirus infection". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 21 (11): 1949–55. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0663. PMC3970163. PMID 23019238.

- ^ Cecil Medicine: Expert Consult Premium Edition . ISBN 1437736084, 9781437736083. Page 1317.

- ^ Berek and Hacker's Gynecologic Oncology. ISBN 0781795125, 9780781795128. Folio 342

- ^ Cronjé HS (February 2004). "Screening for cervical cancer in developing countries". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 84 (2): 101–eight. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2003.09.009. PMID 14871510. S2CID 21356776.

- ^ Sellors, JW (2003). "Chapter 4: An introduction to colposcopy: indications for colposcopy, instrumentation, principles and documentation of results". Colposcopy and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a beginners' manual. ISBN978-92-832-0412-1.

- ^ Pannu HK, Corl FM, Fishman EK (September–October 2001). "CT evaluation of cervical cancer: spectrum of disease". Radiographics. 21 (5): 1155–68. doi:10.1148/radiographics.21.5.g01se311155. PMID 11553823.

- ^ Galaal K, Bryant A, Deane KH, Al-Khaduri M, Lopes Advertising (December 2022). "Interventions for reducing anxiety in women undergoing colposcopy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (12): CD006013. doi:x.1002/14651858.cd006013.pub3. PMC4161490. PMID 22161395.

- ^ a b "Cancer Research United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland website". Archived from the original on xvi January 2009. Retrieved 3 Jan 2009.

- ^ a b c DeMay, Yard (2007). Practical principles of cytopathology. Revised edition. Chicago, IL: American Society for Clinical Pathology Press. ISBN978-0-89189-549-7.

- ^ Garcia A, Hamid O, El-Khoueiry A (6 July 2006). "Cervical Cancer". eMedicine. WebMD. Archived from the original on 9 December 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^ Dolinsky, Christopher (17 July 2006). "Cervical Cancer: The Basics". OncoLink. Abramson Cancer Middle of the University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on xviii January 2008. Retrieved two December 2007.

- ^ Mulita, Francesk; Iliopoulos, Fotios; Kehagias, Ioannis (2020). "A rare case of gastric-blazon mucinous endocervical adenocarcinoma in a 59-twelvemonth-onetime woman". Menopausal Review. xix (3): 147–150. doi:ten.5114/pm.2020.99563. ISSN 1643-8876. PMC7573334. PMID 33100952.

- ^ "What Is Cervical Cancer?". American Cancer Gild.

- ^ "Cervical cancer – Types and grades". Cancer Inquiry United kingdom.

- ^ Bhatla, Neerja; Berek, Jonathan S.; Cuello Fredes, Mauricio; Denny, Lynette A.; Grenman, Seija; Karunaratne, Kanishka; Kehoe, Sean T.; Konishi, Ikuo; Olawaiye, Alexander B.; Prat, Jaime; Sankaranarayanan, Rengaswamy; Brierley, J.; Mutch, D.; Querleu, D.; Cibula, D.; Quinn, M.; Botha, H.; Sigurd, L.; Rice, L.; Ryu, H. South.; Ngan, H.; Mäenpää, J.; Andrijono, A.; Purwoto, Thou.; Maheshwari, A.; Bafna, U. D.; Plante, M.; Natarajan, J. (2019). "Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri". International Periodical of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 145 (1): 129–135. doi:10.1002/ijgo.12749. PMID 30656645. S2CID 58656013.

- ^ Payne N, Chilcott J, McGoogan Eastward (2000). "Liquid-based cytology in cervical screening: a rapid and systematic review". Health Engineering science Assessment. 4 (18): 1–73. doi:10.3310/hta4180. PMID 10932023.

- ^ Karnon J, Peters J, Platt J, Chilcott J, McGoogan Due east, Brewer N (May 2004). "Liquid-based cytology in cervical screening: an updated rapid and systematic review and economic assay". Health Technology Cess. 8 (20): iii, one–78. doi:10.3310/hta8200. PMID 15147611.

- ^ "Liquid Based Cytology (LBC): NHS Cervical Screening Programme". Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved ane October 2022.

- ^ a b c Arbyn M, Anttila A, Hashemite kingdom of jordan J, Ronco G, Schenck U, Segnan N, et al. (March 2022). "European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening. 2d edition—summary document". Annals of Oncology. 21 (3): 448–58. doi:ten.1093/annonc/mdp471. PMC2826099. PMID 20176693.

- ^ Everett T, Bryant A, Griffin MF, Martin-Hirsch PP, Forbes CA, Jepson RG (May 2022). Everett T (ed.). "Interventions targeted at women to encourage the uptake of cervical screening". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (five): CD002834. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002834.pub2. PMC4163962. PMID 21563135.

- ^ a b c "Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines for Average-Risk Women" (PDF). cdc.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on i February 2022. Retrieved eight November 2022.

- ^ a b c Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology (November 2022). "ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 131: Screening for cervical cancer". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 120 (five): 1222–38. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318277c92a. PMID 23090560.

- ^ Karjane N, Chelmow D (June 2022). "New cervical cancer screening guidelines, again". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. forty (2): 211–23. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2013.03.001. PMID 23732026.

- ^ a b Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, et al. (August 2022). "Screening for Cervical Cancer: U.s.a. Preventive Services Chore Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 320 (seven): 674–686. doi:ten.1001/jama.2018.10897. PMID 30140884.

- ^ a b Arrossi S, Temin South, Garland S, Eckert LO, Bhatla N, Castellsagué Ten, et al. (October 2022). "Primary Prevention of Cervical Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Resource-Stratified Guideline". Journal of Global Oncology. 3 (five): 611–634. doi:ten.1200/JGO.2016.008151. PMC5646902. PMID 29094100.

- ^ a b c World Wellness Organization (2014). Comprehensive cervical cancer control. A guide to essential practice - Second edition. ISBN978-92-4-154895-three. Archived from the original on four May 2022.

- ^ Manhart LE, Koutsky LA (November 2002). "Do condoms foreclose genital HPV infection, external genital warts, or cervical neoplasia? A meta-assay". Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 29 (11): 725–35. doi:10.1097/00007435-200211000-00018. PMID 12438912. S2CID 9869956.

- ^ Medeiros LR, Rosa DD, da Rosa MI, Bozzetti MC, Zanini RR (Oct 2009). "Efficacy of human papillomavirus vaccines: a systematic quantitative review". International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. nineteen (7): 1166–76. doi:ten.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a3d100. PMID 19823051. S2CID 24695684.

- ^ a b c The Asahi Shimbun (xv June 2022). "Health ministry building withdraws recommendation for cervical cancer vaccine". The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022.

- ^ Zhang X, Dai B, Zhang B, Wang Z (February 2022). "Vitamin A and risk of cervical cancer: a meta-analysis". Gynecologic Oncology. 124 (2): 366–73. doi:ten.1016/j.ygyno.2011.10.012. PMID 22005522.

- ^ Myung SK, Ju W, Kim SC, Kim H (October 2022). "Vitamin or antioxidant intake (or serum level) and risk of cervical neoplasm: a meta-analysis". BJOG. 118 (11): 1285–91. doi:x.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03032.ten. hdl:2027.42/86903. PMID 21749626. S2CID 38761694.

- ^ "Cervical Cancer Handling Options | Treatment Choices by Stage". www.cancer.org . Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ Baalbergen A, Veenstra Y, Stalpers Fifty (January 2022). "Primary surgery versus main radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy for early adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (one): CD006248. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006248.pub3. PMC7387233. PMID 23440805.

- ^ Einhorn N, Tropé C, Ridderheim M, Boman K, Sorbe B, Cavallin-Ståhl Due east (2003). "A systematic overview of radiation therapy furnishings in cervical cancer (cervix uteri)". Acta Oncologica. 42 (v–vi): 546–56. doi:ten.1080/02841860310014660. PMID 14596512.

- ^ Chemoradiotherapy for Cervical Cancer Meta-analysis Collaboration (CCCMAC) (January 2022). "Reducing uncertainties well-nigh the effects of chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer: individual patient data meta-assay". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (one): CD008285. doi:x.1002/14651858.cd008285. PMC7105912. PMID 20091664.

- ^ Lu D, Wang X, Shi G (March 2022). "Perioperative enhanced recovery programmes for gynaecological cancer patients". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD008239. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008239.pub4. PMC6457837. PMID 25789452.

- ^ van Nagell, J.R.; Greenwell, N.; Powell, D.F.; Donaldson, E.S.; Hanson, M.B.; Gay, E.C. (April 1983). "Microinvasive carcinoma of the neck". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 145 (8): 981–989. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(83)90852-9. ISSN 0002-9378. PMID 6837683.

- ^ Erstad, Shannon (12 Jan 2007). "Cone biopsy (conization) for aberrant cervical cell changes". WebMD. Archived from the original on 19 November 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^ Lin Y, Zhou J, Dai Fifty, Cheng Y, Wang J (September 2022). "Vaginectomy and vaginoplasty for isolated vaginal recurrence eight years after cervical cancer radical hysterectomy: A example report and literature review". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 43 (9): 1493–1497. doi:10.1111/jog.13375. PMID 28691384. S2CID 42161609.

- ^ Kokka F, Bryant A, Brockbank E, Jeyarajah A (May 2022). "Surgical treatment of phase IA2 cervical cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (five): CD010870. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010870.pub2. PMC6513277. PMID 24874726.

- ^ Jones WB, Mercer Become, Lewis JL, Rubin SC, Hoskins WJ (October 1993). "Early on invasive carcinoma of the cervix". Gynecologic Oncology. 51 (1): 26–32. doi:ten.1006/gyno.1993.1241. PMID 8244170.

- ^ Dolson, Laura (2001). "Trachelectomy". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^ a b Burnett AF (February 2006). "Radical trachelectomy with laparoscopic lymphadenectomy: review of oncologic and obstetrical outcomes". Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 18 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1097/01.gco.0000192968.75190.dc. PMID 16493253. S2CID 22958941.

- ^ Cibula D, Ungár L, Svárovský J, Zivný J, Freitag P (March 2005). "[Intestinal radical trachelectomy—technique and experience]". Ceska Gynekologie (in Czech). seventy (two): 117–22. PMID 15918265.

- ^ Plante M, Renaud MC, Hoskins IA, Roy M (July 2005). "Vaginal radical trachelectomy: a valuable fertility-preserving option in the management of early on-stage cervical cancer. A series of l pregnancies and review of the literature". Gynecologic Oncology. 98 (i): iii–10. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.04.014. PMID 15936061.

- ^ Roy M, Plante 1000, Renaud MC, Têtu B (September 1996). "Vaginal radical hysterectomy versus abdominal radical hysterectomy in the treatment of early-stage cervical cancer". Gynecologic Oncology. 62 (3): 336–9. doi:10.1006/gyno.1996.0245. PMID 8812529.

- ^ Dargent D, Martin X, Sacchetoni A, Mathevet P (Apr 2000). "Laparoscopic vaginal radical trachelectomy: a handling to preserve the fertility of cervical carcinoma patients". Cancer. 88 (viii): 1877–82. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000415)88:8<1877::AID-CNCR17>iii.0.CO;2-W. PMID 10760765.

- ^ Schlaerth JB, Spirtos NM, Schlaerth Air-conditioning (January 2003). "Radical trachelectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy with uterine preservation in the handling of cervical cancer". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 188 (1): 29–34. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.124. PMID 12548192.

- ^ a b

- ^ Waggoner SE (June 2003). "Cervical cancer". Lancet. 361 (9376): 2217–25. doi:ten.1016/S0140-6736(03)13778-6. PMID 12842378. S2CID 24115541.

- ^ Falcetta FS, Medeiros LR, Edelweiss MI, Pohlmann PR, Stein AT, Rosa DD (November 2022). "Adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy for early on stage cervical cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD005342. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005342.pub4. PMC4164460. PMID 27873308.

- ^ Nama V, Angelopoulos Thou, Twigg J, Murdoch JB, Bailey J, Lawrie TA (October 2022). "Type II or type III radical hysterectomy compared to chemoradiotherapy as a primary intervention for stage IB2 cervical cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (x): CD011478. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011478.pub2. PMC6516889. PMID 30311942.

- ^ "FDA Approves First Drug Treatment for Late-Stage Cervical Cancer". U.South. Food and Drug Assistants. 15 June 2006. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 2 Dec 2007.

- ^ Moon, Ji Immature; Song, Ik-Chan; Ko, Young Bok; Lee, Hyo Jin (vi April 2022). "The combination of cisplatin and topotecan as a second-line handling for patients with advanced/recurrent uterine cervix cancer". Medicine. 97 (14): e0340. doi:10.1097/Doctor.0000000000010340. ISSN 0025-7974. PMC5902288. PMID 29620661.

- ^ Tangjitgamol Due south, Katanyoo Grand, Laopaiboon M, Lumbiganon P, Manusirivithaya S, Supawattanabodee B (December 2022). "Adjuvant chemotherapy after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced cervical cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD010401. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010401.pub2. PMC6402532. PMID 25470408.

- ^ a b Sardain H, Lavoue V, Redpath M, Bertheuil Northward, Foucher F, Levêque J (August 2022). "Curative pelvic exenteration for recurrent cervical carcinoma in the era of concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy. A systematic review" (PDF). European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 41 (eight): 975–85. doi:ten.1016/j.ejso.2015.03.235. PMID 25922209.

- ^ Lanceley A, Fiander A, McCormack M, Bryant A (Nov 2022). Cochrane Gynaecological, Neuro-oncology and Orphan Cancer Grouping (ed.). "Follow-up protocols for women with cervical cancer subsequently main treatment". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD008767. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008767.pub2. PMID 24277645.

- ^ Eleje GU, Eke Air conditioning, Igberase Become, Igwegbe AO, Eleje LI (March 2022). "Palliative interventions for controlling vaginal haemorrhage in advanced cervical cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (three): CD011000. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011000.pub3. PMC6423555. PMID 30888060.

- ^ "Enforcement Reports" (PDF).

- ^ "Seagen and Genmab Announce FDA Accelerated Blessing for Tivdak (tisotumab vedotin-tftv) in Previously Treated Recurrent or Metastatic Cervical Cancer". Seagen. 20 September 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022 – via Business Wire.

- ^ "Cervical Cancer". Encyclopedia of Women's Wellness.

- ^ "What Are the Key Statistics Almost Cervical Cancer?". American Cancer Club. 4 August 2006. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 2 Dec 2007.

- ^ "Cervical Cancer". Cervical Cancer: Cancers of the Female Reproductive System: Merck Transmission Habitation Edition. Merck Manual Home Edition. Archived from the original on sixteen December 2006. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ "Cervical Cancer". Cervical Cancer: Pathology, Symptoms and Signs, Diagnosis, Prognosis and Handling. Armenian Health Network, Health.am. Archived from the original on vii February 2007.

- ^ "Cervical Cancer: Statistics | Cancer.Net". Cancer.Cyberspace. 25 June 2022. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Cervical cancer statistics and prognosis". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on xx May 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ a b Nygård Thou (June 2022). "Screening for cervical cancer: when theory meets reality". BMC Cancer. 11: 240. doi:ten.1186/1471-2407-11-240. PMC3146446. PMID 21668947.

- ^ Muliira RS, Salas AS, O'Brien B (2016). "Quality of Life among Female Cancer Survivors in Africa: An Integrative Literature Review". Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing. four (1): 6–17. doi:10.4103/2347-5625.199078. PMC5297234. PMID 28217724.

- ^ Dutta, Tapati; Meyerson, Beth; Agley, Jon (2018). "African cervical cancer prevention and control plans: A scoping review". Journal of Cancer Policy. sixteen: 73–81. doi:10.1016/j.jcpo.2018.05.002. S2CID 81552501.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organisation. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ "WHO Fact Sheet on HPV and Cervical Cancer". Earth Wellness System. 24 January 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Kent A (Wintertime 2022). "HPV Vaccination and Testing". Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 3 (i): 33–4. PMC2876324. PMID 20508781.

- ^ Cordeiro CN, Gemignani ML (March 2022). "Gynecologic Malignancies in Pregnancy: Balancing Fetal Risks With Oncologic Safety". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 72 (3): 184–193. doi:ten.1097/OGX.0000000000000407. PMC5358514. PMID 28304416.

- ^ "Incidence and mortality rates". Archived from the original on 12 September 2009.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as title (link) - ^ Hall, Michaela; et al. (2 October 2022). "The projected timeframe until cervical cancer emptying in Australia: a modelling study". Lancet. Retrieved eight November 2022.

- ^ MacDonald Northward, Stanbrook MB, Hébert PC (September 2008). "Human papillomavirus vaccine risk and reality". CMAJ (in French). 179 (6): 503, 505. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081238. PMC2527393. PMID 18762616.

- ^ National Cancer Registry Programme under Indian Council of Medical Research Reports

- ^ Krishnatreya M, Kataki Ac, Sharma JD, Nandy P, Gogoi G (2015). "Clan of educational levels with survival in Indian patients with cancer of the uterine neck". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 16 (8): 3121–three. doi:x.7314/apjcp.2015.xvi.viii.3121. PMID 25921107.

- ^ "Cervical cancer statistics". Cancer Research Uk. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ "Cancer Stat Facts: Cervical Cancer". National Cancer Institute SEER Program . Retrieved four June 2022.

- ^ a b Armstrong EP (Apr 2022). "Prophylaxis of cervical cancer and related cervical affliction: a review of the price-effectiveness of vaccination confronting oncogenic HPV types". Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. sixteen (3): 217–30. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.3.217. PMID 20331326. S2CID 14373353.

- ^ zur Hausen H (May 2002). "Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application". Nature Reviews. Cancer. ii (5): 342–50. doi:10.1038/nrc798. PMID 12044010. S2CID 4991177.

- ^ Beachler DC, Kreimer AR, Schiffman M, Herrero R, Wacholder S, Rodriguez AC, et al. (January 2022). "Multisite HPV16/18 Vaccine Efficacy Against Cervical, Anal, and Oral HPV Infection". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 108 (1): djv302. doi:10.1093/jnci/djv302. PMC4862406. PMID 26467666.

- ^ Kreimer AR, Herrero R, Sampson JN, Porras C, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, et al. (August 2022). "Evidence for unmarried-dose protection by the bivalent HPV vaccine-Review of the Costa Rica HPV vaccine trial and hereafter inquiry studies". Vaccine. 36 (32 Pt A): 4774–4782. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.078. PMC6054558. PMID 29366703.

- ^ Menczer J (February 2003). "The low incidence of cervical cancer in Jewish women: has the puzzle finally been solved?". The State of israel Medical Association Periodical. 5 (ii): 120–3. PMID 12674663. Archived from the original on eight December 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Heins HC, Dennis EJ, Pratthomas HR (October 1958). "The possible part of smegma in carcinoma of the cervix". American Periodical of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 76 (four): 726–33, word 733–5. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(58)90004-viii. PMID 13583012.

- ^ Alexander ER (June 1973). "Possible etiologies of cancer of the neck other than herpesvirus". Cancer Inquiry. 33 (6): 1485–ninety. PMID 4352386.

- ^ Rosenblatt A, Guidi HG (vi Baronial 2009). Homo Papillomavirus: A Practical Guide for Urologists. Springer Science & Concern Media. ISBN9783540709749.

- ^ Dürst M, Gissmann L, Ikenberg H, zur Hausen H (June 1983). "A papillomavirus Dna from a cervical carcinoma and its prevalence in cancer biopsy samples from different geographic regions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 80 (12): 3812–5. Bibcode:1983PNAS...lxxx.3812D. doi:ten.1073/pnas.eighty.12.3812. PMC394142. PMID 6304740. .

- ^ Lowy DR, Schiller JT (May 2006). "Prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines". The Periodical of Clinical Investigation. 116 (five): 1167–73. doi:10.1172/JCI28607. PMC1451224. PMID 16670757.

- ^ McNeil C (April 2006). "Who invented the VLP cervical cancer vaccines?". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 98 (seven): 433. doi:x.1093/jnci/djj144. PMID 16595773.

- ^ "WHO rolls out plan to rid world of cervical cancer, saving millions of lives". UN News. xvi Nov 2022. Retrieved 27 Nov 2022.

- ^ Cancer Constitute NSW (2013). "Information about cervical screening for Ancient women". NSW Authorities. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022.

- ^ a b Mary-Anne Romano (17 October 2022). "Aboriginal cervical cancer rates parallel health inequity". Science Network Western Australia. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022.

- ^ Australian Cervical Cancer Foundation. "Vision and Mission". Australian Cervical Cancer Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022.

- ^ Australian Cervical Cancer Foundation. "Our People". Australian Cervical Cancer Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022.

- ^ Gillian Bradford (16 October 2006). "Janette Howard speaks on her battle with cervical cancer". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022.

- ^ Tiro JA, Meissner How-do-you-do, Kobrin S, Chollette V (February 2007). "What practice women in the U.S. know about human papillomavirus and cervical cancer?". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 16 (2): 288–94. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0756. PMID 17267388.

- ^ Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Edwards BK (September 2004). "Persistent area socioeconomic disparities in U.S. incidence of cervical cancer, bloodshed, stage, and survival, 1975–2000". Cancer. 101 (5): 1051–seven. doi:ten.1002/cncr.20467. PMID 15329915. S2CID 26033629.

Further reading [edit]

- Arbyn One thousand, Castellsagué X, de Sanjosé Due south, Bruni L, Saraiya M, Bray F, Ferlay J (December 2022). "Worldwide burden of cervical cancer in 2008". Annals of Oncology. 22 (12): 2675–86. doi:ten.1093/annonc/mdr015. PMID 21471563.

- Chuang LT, Temin Due south, Camacho R, Dueñas-Gonzalez A, Feldman Due south, Gultekin M, et al. (Oct 2022). "Direction and Care of Women With Invasive Cervical Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Resource-Stratified Clinical Practice Guideline". Journal of Global Oncology. ii (5): 311–340. doi:10.1200/JGO.2016.003954. PMC5493265. PMID 28717717.

- Peto J, Gilham C, Fletcher O, Matthews Fe (2004). "The cervical cancer epidemic that screening has prevented in the UK". Lancet. 364 (9430): 249–56. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16674-nine. PMID 15262102. S2CID 11059712.

- Pimenta JM, Galindo C, Jenkins D, Taylor SM (November 2022). "Estimate of the global burden of cervical adenocarcinoma and potential bear upon of prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccination". BMC Cancer. 13 (1): 553. doi:x.1186/1471-2407-thirteen-553. PMC3871005. PMID 24261839.

- Bhatla Due north, Aoki D, Sharma DN, Sankaranarayanan R (October 2022). "Cancer of the neck uteri". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 143 Suppl 2: 22–36. doi:10.1002/ijgo.12611. PMID 30306584.

External links [edit]

- Cervical cancer at Curlie

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cervical_cancer

Posted by: stewartonves1995.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Find Out Cervical Cancer"

Post a Comment